chevron_left

-

play_arrow

NGradio So good... like you

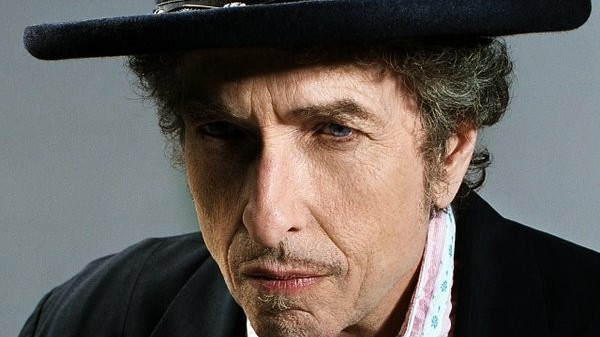

In 1993, Bob Dylan released World Gone Wrong, an album of cover versions of what might be called pre-modern songs by some of the early blues and folk performers that he revered. Dylan’s sleeve notes for the album are a thing of wonder in themselves: short, sometimes surreal riffs on the timeless quality of stark and mysterious songs that sound old as the hills but, as his writing pointed out, possessed a deep contemporary resonance.

Despite its high-flown and somewhat misleading title, The Philosophy of Modern Song is a kind of strange companion to those sleeve notes rather than a philosophical treatise on the art and craft of songwriting. Illustrated with a wealth of sometimes tangentially linked photographs (publicity stills, snapshots, landscapes and classic documentary images by the likes of Dorothea Lange and William Klein), it comprises 66 deeply subjective essays on songs Dylan holds dear, from standards and groundbreakers to obscurities and oddities.

Often, the juxtapositions are extreme: Bing Crosby’s charming but very odd ditty Whiffenpoof Song rubs shoulders with the Clash’s punk rock anthem London Calling. The formal brilliance of Jimmy Webb’s By the Time I Get to Phoenix is celebrated alongside the wild, untrammelled energy of rockabilly pioneers such as Sonny Burgess. The sophisticated soul of Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes gives way to the gothic thrust of Johnny Paycheck, whom Dylan describes as “the outlaw all the other country singers claimed to be”. (One of his songs is called (Pardon Me) I’ve Got Someone to Kill.)

There are surprises aplenty, not least the almost sacrilegious absence of a single song by the Beatles – are there any songwriters more “modern” than Lennon and McCartney? Dylan, though, has never been an anglophile, or an artist much impressed by elaborate studio techniques or groundbreaking sonic invention – Brian Wilson does not appear either. No Carole King or Joni Mitchell songs, but Nina Simone is rightly hymned for her “measured defiant delivery” of Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood.

Judy Garland is also here alongside Rosemary Clooney and Cher – good to see Gypsys, Tramps and Thieves receiving its due, with Dylan quipping that it “could easily be the answer to the question, ‘Name three types of people you’d like to have dinner with’”.

His selections are mostly American (the exceptions being the Who, the Clash and Elvis Costello) and tend towards the unapologetically old fashioned, whether that be the rough and rowdy roots music that he has always been drawn to – blues, rockabilly, bluegrass, early folk – or the pre-pop standards he has homaged on his recent trio of cover albums. There are quite a few crooners featured here: Perry Como, Vic Damone, Dean Martin and, inevitably, Frank Sinatra, though Strangers in the Night seems an oddly lightweight choice – Sinatra himself hated it. It does however give Dylan a chance to trace the song’s “murky” history: the authorship of both the melody and the lyrics are contested. It’s that kind of book: discursive, unpredictable, but always illuminating. Characteristically Dylan, in fact.

Intriguingly, several of the essays are also accompanied by more imaginative “riffs” in which Dylan evokes the atmosphere or emotional resonance of a lyric by stepping inside the mind of the narrator and, by extension, the songwriter. Of the Who’s My Generation, he writes: “In this song people are trying to slap you around, slap you in the face, vilify you. They’re rude and slam you down, take cheap shots. They don’t like you because you pull out all the stops and go for broke.” From there, though, he goes on to uncover several layers of emotional complexity – defensiveness, grievance, insecurity – that are all but masked by the song’s arrogant amphetamine attitude.

Most of the time, this iconoclastic approach makes for heady and exhilarating stuff, though his reading of Hank Williams’s classic country ballad Your Cheatin’ Heart strikes me as wilfully perverse. Williams wrote it as a bruised response to his ex-wife’s infidelities, but Dylan sees it as “the song of a con artist… the swindler who sold me a faulty bill of goods”, a crook whose cheatin’ heart “brought poison and pestilence into the home of millions”. Even as a metaphor for romantic betrayal, that’s quite a leap of interpretation.

His selections are mostly American (the exceptions being the Who, the Clash and Elvis Costello) and tend towards the unapologetically old fashioned, whether that be the rough and rowdy roots music that he has always been drawn to – blues, rockabilly, bluegrass, early folk – or the pre-pop standards he has homaged on his recent trio of cover albums. There are quite a few crooners featured here: Perry Como, Vic Damone, Dean Martin and, inevitably, Frank Sinatra, though Strangers in the Night seems an oddly lightweight choice – Sinatra himself hated it. It does however give Dylan a chance to trace the song’s “murky” history: the authorship of both the melody and the lyrics are contested. It’s that kind of book: discursive, unpredictable, but always illuminating. Characteristically Dylan, in fact.

Intriguingly, several of the essays are also accompanied by more imaginative “riffs” in which Dylan evokes the atmosphere or emotional resonance of a lyric by stepping inside the mind of the narrator and, by extension, the songwriter. Of the Who’s My Generation, he writes: “In this song people are trying to slap you around, slap you in the face, vilify you. They’re rude and slam you down, take cheap shots. They don’t like you because you pull out all the stops and go for broke.” From there, though, he goes on to uncover several layers of emotional complexity – defensiveness, grievance, insecurity – that are all but masked by the song’s arrogant amphetamine attitude.

Most of the time, this iconoclastic approach makes for heady and exhilarating stuff, though his reading of Hank Williams’s classic country ballad Your Cheatin’ Heart strikes me as wilfully perverse. Williams wrote it as a bruised response to his ex-wife’s infidelities, but Dylan sees it as “the song of a con artist… the swindler who sold me a faulty bill of goods”, a crook whose cheatin’ heart “brought poison and pestilence into the home of millions”. Even as a metaphor for romantic betrayal, that’s quite a leap of interpretation.

Spurce: theguardian.com

Written by: New Generation Radio

Rate it

Similar posts

ΔΗΜΟΦΙΛΗ ΑΡΘΡΑ

COPYRIGHT 2020. NGRADIO

Post comments (0)