chevron_left

-

play_arrow

NGradio So good... like you

There are as many ways to approach an artist’s story as there are to compose a song. But music memoirs and biographies typically follow a template — the humble beginnings, the meteoric rise and the (possibly substance-related) fall, followed by a hard-won recovery with various star-studded encounters along the way.

This fall, the latest crop of music biographies stands out in a crowded field for how well they find new wrinkles within that formula.

Here are five of the best:

“Blood” by Allison Moorer

Moorer doesn’t just explore the arc of a musician’s life as much as the indelible moments that both shatter and define it. The Alabama-born singer-songwriter was 14 when her father shot and killed her mother on their lawn before turning the gun on himself. With searching, poetic language, Moorer unflinchingly ventures into the dark shadows of that day — and a childhood haunted by alcoholism and abuse — with sorrow, hard-won resilience and, ultimately, compassion.

Her intimate, in-progress processing of the trauma is as affecting as it is jarring. The book begins with her requesting her parents’ autopsy reports in 2017. Later, recounting the first time she saw her father strike her older sister (fellow singer-songwriter Shelby Lynne), Moorer confesses, “Writing that down makes me feel like someone has placed an anvil on my chest. There is nothing that can make me feel better or less guilty or shamed as I see the words about him hitting her staring back at me … I just hurt, on the inside and even out. There’s something metallic and cold under my skin.”T

The 47-year-old Moorer barely touches on her music, apart from nods toward collaborations with her sister and recollections of more peaceful nights with her family spent harmonizing together. But “Blood” leaves behind a powerful need to hear more. (Da Capo, $27)

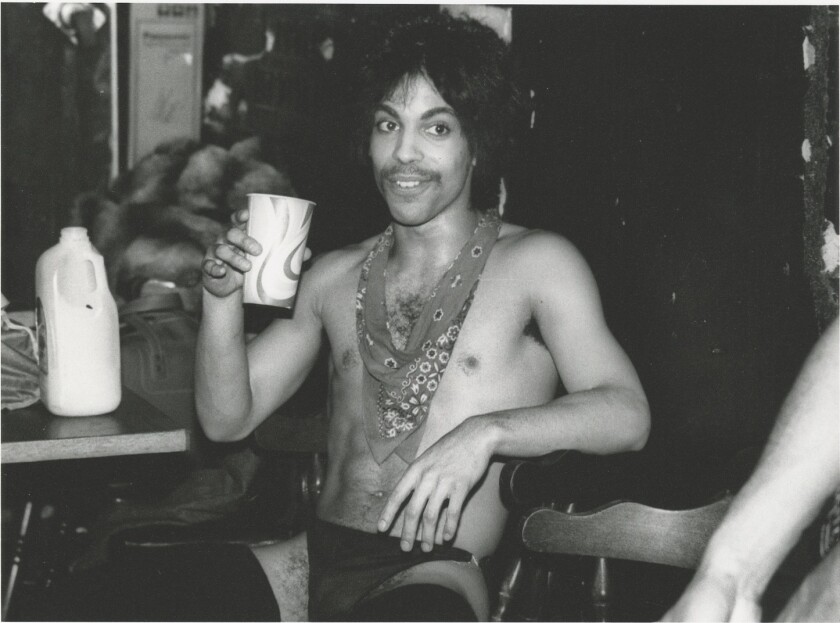

“The Beautiful Ones” by Prince

Inevitably, “The Beautiful Ones” is shaped by a powerful absence. The book was overseen by Paris Review editor Dan Piepenbring, who was in his late 20s when Prince chose him to collaborate on what he envisioned as “the biggest music book of all time.” The project was still in progress when the singer died in 2016 at age 57.

As a result, only 20 pages of Prince’s story exist here in a blend of colorful remembrances of growing up in Minneapolis and the performer’s complicated relationship with his parents. In an illuminating, heartfelt introduction, Piepenbring describes other ideas discussed with the famously idiosyncratic artist, including Prince’s views on funk, black self-sufficiency and, tantalizingly, an unshared anecdote about a near collaboration with Michael Jackson. “There’s going to be some bombshells,” Prince teased at one point. “I hope people are ready.”

The rest of “The Beautiful Ones” is a sprawling collection of photos and ephemera recovered from Prince’s estate, along with his original treatment for “Purple Rain,” all of which will count as essentials for his biggest fans. The book resembles more a “piece of tour merchandise” that Prince said he wanted to avoid than the category-defying barn burner he surely imagined. Another goal, however, was to build upon his already burgeoning mystery. On that front, the book feels like a success. (Spiegel & Grau, $30)

“Acid for the Children” by Flea

Flea’s book closes sooner than may be expected, with the formation of his platinum-selling band, the Red Hot Chili Peppers (a second volume is in the works, according to the book’s closing note). The memoir’s 380 pages may be a lot of time to spend with a pre-fame Michael Peter Balzary, who adopted the name Flea while coming up in the L.A. punk scene. But “Acid for the Children” carries such an earnest, even delirious love for music — alongside a self-effacing but engaging stream-of-consciousness delivery — that adolescent Michael remains terrific company regardless.

Flea grew up with a jazz musician stepfather and a disengaged mother amid a steady supply of creativity and chaos, formative years shaped by all manner of music and musicians. That included pianist Freddie Redd and L.A. composer Horace Tapscott, whose community focus would later inspire Flea to found the Silverlake Conservatory of Music in 2001.

With its occasional slang spellings and bebop flights of fancy alongside ample tales of teenage bad ideas (“I was nothing but an obnoxious, offensive jerk,” Flea confesses after recounting one ill-advised prank), the book may — like all music biographies — be best suited for ardentfans. But “Acid for the Children” remains a vital, only-in-L.A. account of a wide-open time filtered through an engaging, humbled voice reshaped by his recovery and reconnecting to his spirit through art and music. (Grand Central Publishing, $30)

Me” by Elton John

“Me” recounts the singer-songwriter’s life, from growing up in suburban London through his electric partnership with songwriter Bernie Taupin to last year’s announcement of his retirement from touring. And while typical music-bio beats are in full force here, John’s dryly witty voice remains an ideal guide through every up and down.

He offers an endearingly grounded look back at both his L.A. breakthrough and a bit of sheepishness glimpse at the excesses of his ‘70s live shows (“For the benefit of anyone who felt this was too subtle and understated, 400 white doves were meant to fly out of the grand pianos,” he recalls of a 1973 Hollywood Bowl performance).

The book touches on darkness as well. John describes his turbulent relationship with his mother, his long and destructive cocaine use and a later turn to activism after meeting young AIDS patient Ryan White. But what lingers most is John’s sure hand with a funny story: He recalls friendships with John Lennon, Freddie Mercury and, most notably, Rod Stewart, who serves as his comic foil in a series of playful efforts to upstage one another with pranks, usually while using their drag names (John is Sharon to Stewart’s Phyllis). (Henry Holt, $30)

“Janis: Her Life and Music” by Holly George-Warren

In a story shaped by encounters with music legends of her time, this new Janis Joplin biography carries a tragic air in building to the singer’s accidental 1970 overdose. Part of the grim, ‘60s-era roster of talented musicians who succumbed to various overindulgences, Joplin’s fully formed character emerges due to the meticulous research and interviews by George-Warren, who also wrote a biography of Big Star’s Alex Chilton.

Joplin, who died at age 27, rises from the page through the recounting of her effervescent notes to her family. The notes show as much of a free spirit as someone driven by ambition to make it in the music industry while fighting the insecurity and fatalistic tendencies that fueled Joplin’s addictions. Encounters with Ron “Pigpen” McKernan and Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead and Peter Coyote from his days with the activist group the Diggers are equally illuminating, as is a rather rich dismissal of her work by Mick Jagger, who reportedly refused to see her London show, saying, “If I want to hear black singing, then I’ll listen to black singers.”

Joplin’s appropriation of a blues sound forged by idol Bessie Smith comes up a few times, alongside defenses from Buddy Guy and B.B. King. “Janis” also recounts her on-tour romantic exploits with Leonard Cohen, Kris Kristofferson and Jim Morrison, who she apparently struck with a bottle more than once. Ultimately, the book successfully argues that Joplin’s full-throated influence reaches much further than her unfortunate end. (Simon & Schuster, $28.99)

Source: latimes.com

Written by: New Generation Radio

Similar posts

ΔΗΜΟΦΙΛΗ ΑΡΘΡΑ

COPYRIGHT 2020. NGRADIO

Post comments (0)